8 is the new 10! (or, how to have a success mindset)

A genius, an elite rock climber, and an Olympian walk into a bar. Sure, it sounds like the classic setup of a joke. The truth is, however, that if these three really did walk into a bar together, you’d probably want to eavesdrop on their conversation. If so, this is almost certainly because they seem like interesting, non-conventional people. Unlike folks in sales, when these three people answer the question “what do you do for a living,” you’d actually like to hear more about it.

Geniuses, rock climbers, and Olympic athletes occupy that rarified space of people who hit the sweet spot of Western, modern values: uniqueness, success, and enviable ability. You see these qualities in many of the figures we lionize and for whom a mythology develops – people like Steve Jobs and Stephen Hawking, and Stephen Curry. In each of these cases (and in the instance of some people not named Steven), it is tempting to believe that all of them were dealt a better hand of cards at birth, where talent is concerned. They are simply smarter, more athletic, or more creative than the rest of us.

This idea that we attribute the behavior of others to their stable personality qualities is one of the greatest findings in the history of psychology. It is known as the “fundamental attribution error,” and it especially applies to so-called “bad behavior.” When a person cuts you off on the highway, it is because they are a jerk, but when you do it to someone else, it is because you are temporarily distracted. The bottom line, psychologically speaking, is that other people behave badly because of who they are, and you behave badly because of circumstances.

What if we turn this idea on its head and ask about good behavior, like success? We are more likely to attribute the success of others to talent than we are to luck, opportunity, or social support, which is why I was so curious to ask successful people about qualities other than their natural intelligence or ability. In particular, I was curious to find out if successful people think differently than do the rest of us. Do they have a particular mindset, or do they have mental tricks that help them accomplish their goals?

I don’t pretend to have a definitive answer to these questions, but I was able to get some insights by interviewing 3 highly successful people. That’s right: a genius, an elite rock climber, and an Olympian.

Post quick links:

“Am I successful?”: Angela Duckworth

Because we are– here—primarily concerned with the psychological aspects of success, it makes sense, to begin with the first of my three interviews: Angela Duckworth. Angela, a psychologist, has spent the bulk of her career teasing apart exactly this topic—success– through her study of “grit.” She is interested in, among other things, the mental aspects of success above and beyond natural talent, privilege, and luck. At the risk of boiling down her entire career to a single sentence, she has found that people who have a passion for a topic and persevere in it are more likely to be successful.

When I interviewed her, I desperately did not want to ask her, “Do you have grit?” I can imagine the number of times she has had to answer exactly that query, and I am guessing that she would persevere with our interview but without much passion. Instead, I asked, “what mental habits do you have that have positively influenced your success?” Spoiler alert: she did not say passion or perseverance.

“I am never satisfied with anything,” she said.

She described a deep desire to improve her work, and she admitted that this mindset could sometimes cause her to charge forward without savoring successes. This was on full display when she challenged the very notion that she should be considered successful at all or deserves to be interviewed. Mind you, this was not false humility. She seemed genuinely unaware of how inspiring she is. She has won the prestigious McArthur “genius” Award, she studied at Harvard and Oxford, she is an endowed professor at an Ivy League university, and she wrote a best-selling book. Oh yeah, her TED talk has more than 21 million views, and she hosts a podcast with best-selling author Stephen Dubner (Freakonomics).

Angela went on to describe her attitude in greater depth. She was careful to distinguish it from perfectionism. “That can lead to improvement paralysis,” she explained. Instead, she described her attitude as a balancing act where, on the one hand, she cares so deeply about the quality that she wants to improve, and—on the other hand—she wants to feel satisfied with her contribution and move on to the next project. She described it as being an 8 out of 10 on satisfaction.

It turns out that this concept—sometimes called the “magic 8” or the “optimal 8” — is supported by research. Angela already knows this. After all, she is a genius.

Kaizen and the Optimal 8

There is a Japanese word kaizen that means improvement. In the business context, the concept of kaizen is well-known for a more specific meaning: continuous improvement. It is a desire to continue developing without end. You can see it especially in software, in which developers are regularly upgrading. In fact, the label “developer” suggests on-going improvement.

On reflection, the idea of continuous improvement suggests—as illustrated by Angela Duckworth’s example—a sort of low-lying dissatisfaction. By “low-lying,” I mean that it doesn’t rise to the level of a complaint. Instead, it is an acknowledgment that there is yet room for growth. People who have this attitude are generally satisfied but never perfectly satisfied. Further, they tend to be pretty okay with that.

Research reveals that when it comes to accomplishment, it is generally an 8 out of 10 on satisfaction that is associated with the best results. For example, people who are an 8 (rather than a 10) have the best educational performance and are the most politically active. Their neighbors, at a 9 (not a 10), earn the highest incomes. Where accomplishment is concerned, being perfectly satisfied might lead to a slight dip in drive and motivation.

“I hope I am successful!”: Maya Madere

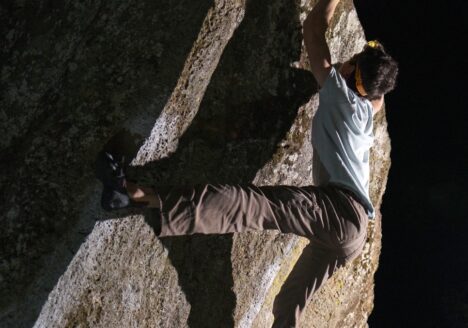

If you aren’t a rock climber, you probably haven’t heard of Maya Madere. If you are—and especially if you are an American climber—then you likely have. Maya grew up in climbing gyms participating in the competition climbing scene (yeah, that’s a thing). In 2016, she placed first in the nation as a youth competitor. She went on to earn third place in the Youth World Championships. Today, she climbs outdoors and competes on the professional circuit while also attending Stanford University.

Maya has all the qualities you would expect from a successful athlete at the elite level: she is highly driven, naturally athletic, and enviably fit. At her level of performance, however, those qualities are commonplace.

One of the factors that best distinguishes performance is attitude. Maya described herself to me as a person who has on-going struggles with self-belief. “I struggle with confidence, optimism, self-worth, and motivation,” she admitted to me. “I am often convinced I do not have what it takes to achieve my goals.” She told me that stress and poor performance can send her into a downward spiral of anger and disappointment.

Indeed, as a climber myself, I am aware that disappointment is common. The weather often interferes with climbing. There are “high gravity days” in which your body seems weaker than normal. There are climbs with tricky sequences of movement that can feel like an unsolvable puzzle. These tough days are a choice-point: will you persevere or give up?

Although it might sound like Maya is poised to give up, she is actually high in hope. Psychologists define hope as a combination of mental attitudes: a belief in one’s own ability (called “agency thinking”) and a recognition that there are multiple routes to solving a problem (called “pathways thinking”). When a person has both of these, she is hopeful, and this, in turn, is directly linked with success. Psychologist Lewis Curry and his colleagues examined the hope mindset of hundreds of Division 1 college athletes to better understand the effect that mindset has on performance. They found that student athletes who believed they were capable and who thought there were multiple routes to achieving a goal had better athletic performance and higher grade-point averages.

In Maya’s case, she has a healthy dose of overarching belief in herself. She knows she is naturally talented and can easily point to evidence of her climbing prowess. Critically, she is also high in pathways thinking. She says she develops coping strategies for the tough days and, when they fail, she develops new ones. “I am reluctant to give up,” she said, “which helps me continue trying to overcome challenges.”

“I don’t care if you think I am successful”: Allison Wagner

Now, we find ourselves in the last lap of this article, sprinting toward the finish line. Not unlike the Olympic swimmer Allison Wagner, when she won the silver medal in the 400-meter individual medley. Interestingly, the Olympic medal may not be Allison’s greatest achievement. She also set a world record time in the 200-meter medley that held for 14 years. To put that in perspective, of the 20 major women’s swimming events, the World Record for 16 of them have been set in the last five years. World records don’t last long, and Allison’s is noteworthy for its longevity.

As if those feats were not enough, Michael Phelps’ coach sought Allison to thank her for developing the flip-turn that he (and virtually all elite swimmers) uses. It is called the “suicide turn” because it requires swimmers to push to the absolute limits of their lung capacity, but it is a faster turn and confers a slight time advantage to elite swimmers. Allison invented that.

It turns out that the suicide turn was the result of a personal quality that influenced Allison’s success in sport: the desire to improve. Like Angela Duckworth, Allison harbors a sense that she can do better. It is that same low-level dissatisfaction that motivates her to train harder and longer. To, in Allison’s words, “out-suffer others.” In Angela’s line of work—research—the disquiet can be a lynchpin for new ideas or a gateway to new topics of study. In Allison’s circumstances, this hunger for improvement often manifested as experimentation.

Allison used the words “improvise” “experiment” and “improve” repeatedly during our interview. During the peak of her swim career, Allison believed that there were new and better ways to get things done. It is here, in her pathways thinking, that you can see a similarity to Maya Madere. Allison believes in alternative routes to accomplishing goals. She lugged a weight machine to Hong Kong despite the fact that it raised eyebrows among her teammates. She eschews the familiar headphone/screen routine during airport layovers and opts to stretch instead. She invents visionary new flip turns.

Experimentation, when applied well, can have performance benefits. In one study of elite figure skaters, for instance, taking an improvisation course improved their skating. After taking comic and theatrical improvisation with Cirque du Soliel, half of the skaters in the study improved between 5 and 11% in their competition scores. What’s more, the vast majority of the athletes reported greater self-acceptance, focus, open-mindedness, the fluidity of movement, and a desire to try new things.

Success for the rest of us

It is often inspiring to thrill at the rarified feats of billionaires and champions. We get stars in our eyes and marvel at the raw talent to which we bear witness. Fortunately, these three contemporary success stories paint a slightly different picture of excellence. Sure, they are loaded with talent but talent is a dime a dozen. Just attend a high school art show or a children’s gymnastics meet; there is plenty of talent out there.

What Angela, Maya, and Allison teach us is an alternative narrative to the one we often hear about Elon, Steve, and LeBron. It is mindset that matters, other things being equal. This is good news for the rest of us. I know I won’t be doing “suicide turns” anytime soon, nor will I be receiving a McArthur genius grant. I can, however, engage in pathways thinking and improve through experimentation. And that improvement can be a continuous improvement—even while being generally (but not totally) satisfied. It is a success lesson for everyday people: 8 is the new 10.